River Nyando Floods and Chinese Wars Over the Koru-Soin Dam Project

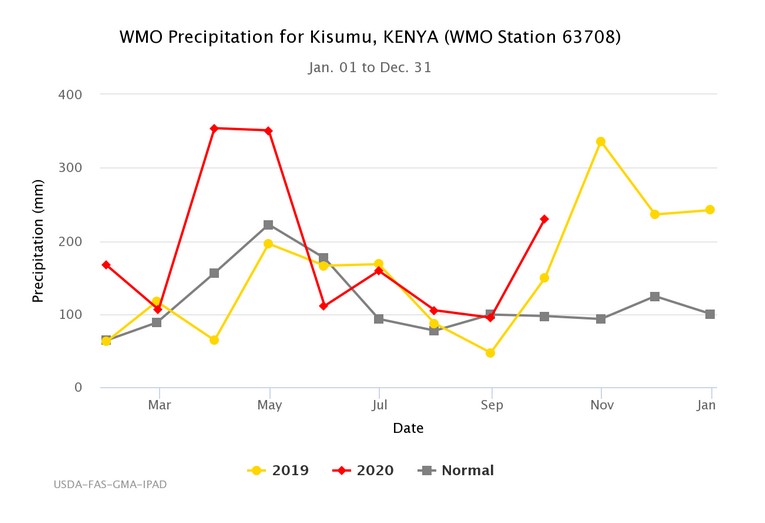

As the two Chinese firms fight over the Koru-Soin dam tender, taxpayers are suffering: their houses submerged, property destroyed, agricultural produce washed away, schools closed, learning disrupted, and thousands of households displaced, surviving under the mercy of emergency relief.