Unmourning the Queen from Kenya

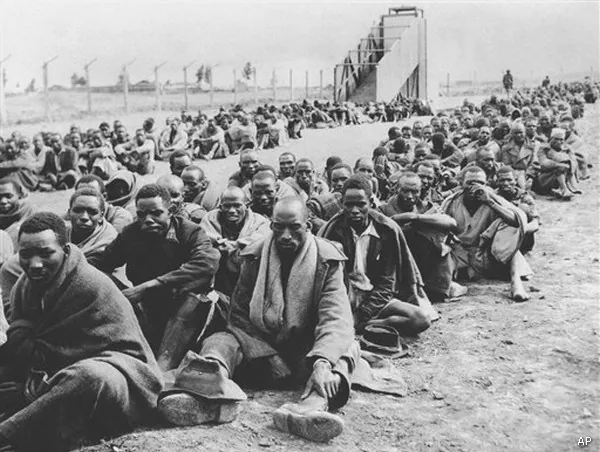

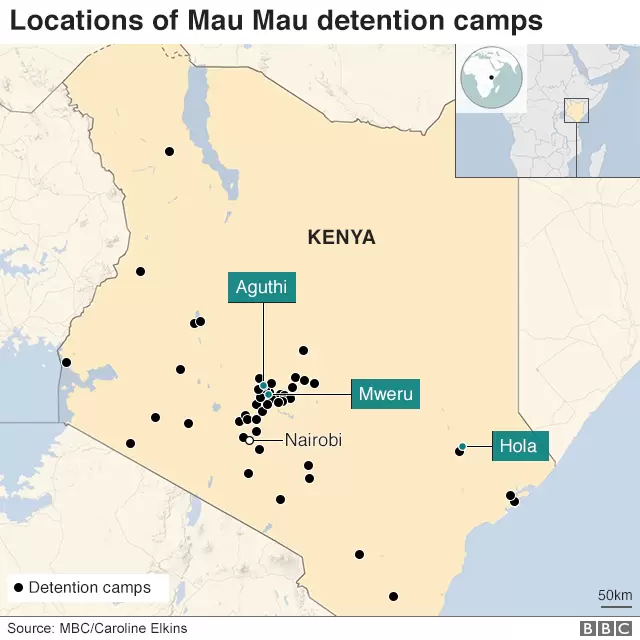

Lukenya camp was sufficiently away from Nairobi and atrocities continued in relative secrecy for a prolonged period, even as Queen Elizabeth II rode past in lovely cars to Treetops Hotel in Central Kenya, for a romantic adventure and delightful service from supposedly happy natives.