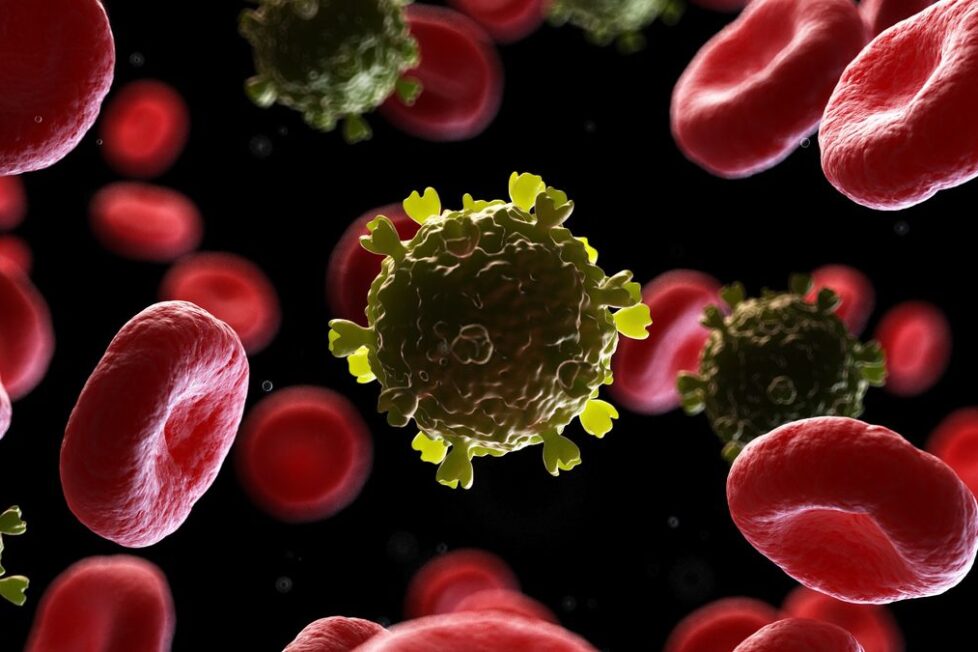

7th Person Cured Of HIV After Stem Cell Transplant Meant to Cure Acute Myeloid Leukemia

A 60-year-old German man, who received a stem cell transplant in 2015 to treat acute myeloid leukemia, now appears to have achieved long-lasting remission of HIV after discontinuing antiretroviral therapy in 2018.