Donald Trump Is Erasing Black History, But Blood Cotton Clothing Won’t Let Him

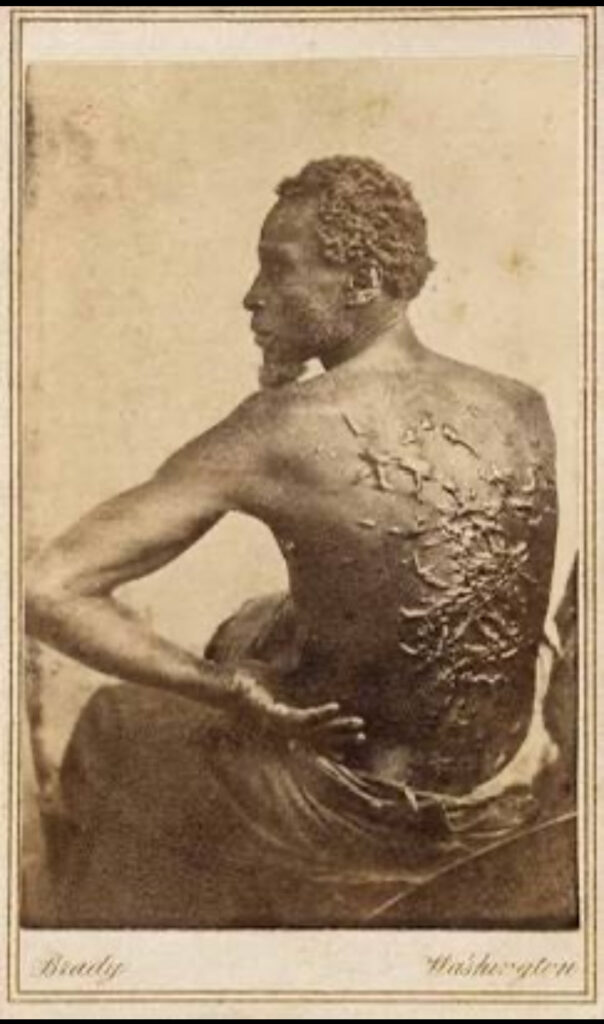

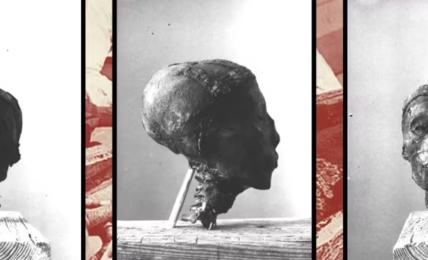

The Whipped P exhibit was created to educate people of all cultures and backgrounds. More importantly, it was designed to help bridge the gap between Africans and African Americans.