Epstein-Barr Virus May Trigger Lupus: New Study Shows How a Common Virus Rewires Immune Cells

A common virus that infects most people worldwide is now implicated in triggering Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus).

A common virus that infects most people worldwide is now implicated in triggering Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus).

A common virus that infects most people worldwide is now implicated in triggering Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus). Scientists at Stanford Medicine and their collaborators report strong new evidence that the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) can reprogram immune cells to initiate the cascade of immune malfunction that defines lupus. The findings, published on November 12 2025 in Science Translational Medicine, may resolve a decades-old mystery about what triggers this devastating disease.

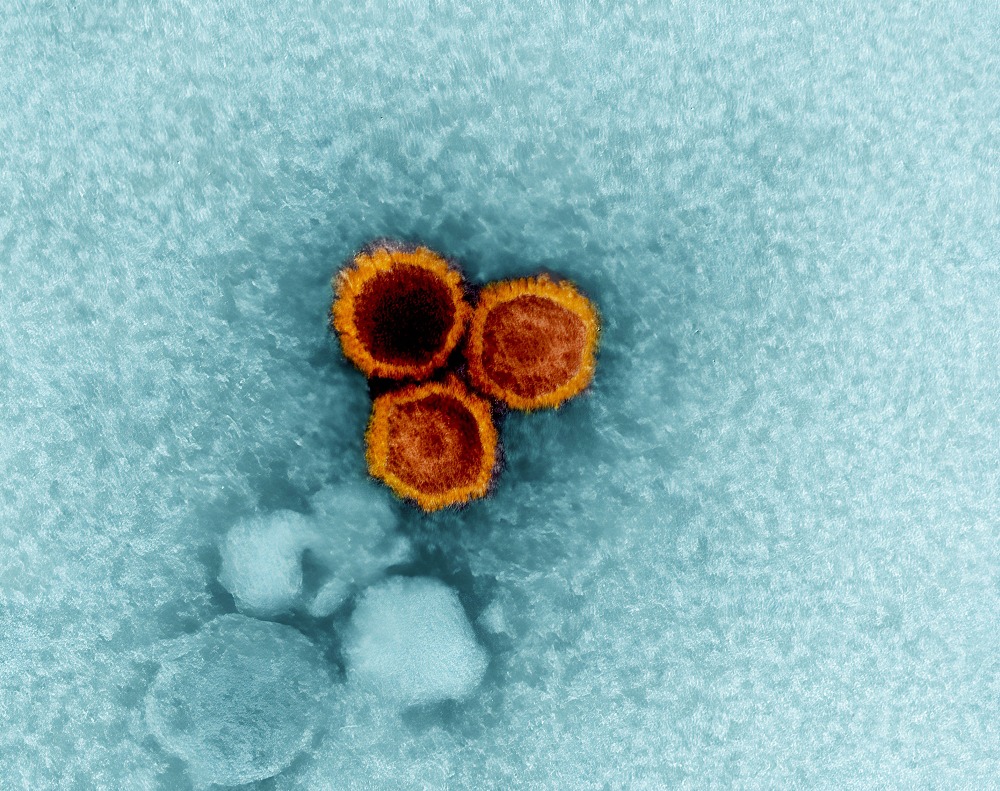

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), also known as human herpesvirus 4, is a member of the herpes virus family. It is one of the most common human viruses. EBV is found worldwide and is a common cause of viral pharyngitis, especially in young adults. Most people get infected with EBV at some point in their lives without even knowing it. EBV spreads most commonly through bodily fluids, primarily saliva. EBV can cause infectious mononucleosis, also called mono, and other illnesses.

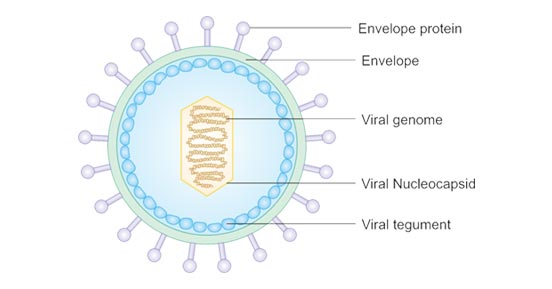

Epstein-Barr virus is about 122–180 nm in diameter and is composed of a double helix of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) which contains about 172,000 base pairs and 85 genes. The DNA is surrounded by a protein nucleocapsid, which is surrounded by a tegument made of protein, which in turn is surrounded by an envelope containing both lipids and surface projections of glycoproteins, which are essential to infection of the host cell.

EBV infects an estimated 95 percent of adults worldwide. For most people EBV remains latent and harmless after initial infection. That prior observation made the repeated link between EBV exposure and higher lupus risk puzzling. But the new study reveals how EBV can shift from silent resident to autoimmune instigator.

Using a novel single-cell sequencing platform able to detect EBV in individual B cells, the research team compared blood samples from 11 people with lupus and 10 healthy controls. They found EBV-infected B cells were dramatically more common in lupus patients — about one infected B cell in every 400, compared with fewer than one in 10,000 in healthy controls.

Importantly the infected B cells were often autoreactive. That means they were capable of producing antibodies that bind the body’s own proteins or DNA — the hallmark of autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

Under normal conditions B cells identify and respond to foreign pathogens by producing antibodies. In lupus the immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues, damaging skin, joints, kidneys, brain and other organs. The new research shows EBV may turn B cells that would otherwise be harmless or dormant into “driver” cells of autoimmunity.

Specifically EBV-infected B cells in lupus patients expressed genetic markers consistent with antigen-presenting cells rather than simple antibody producers. The study identified upregulation of genes such as ZEB2 and TBX21 (T-bet), and signs of chromatin changes indicating activation of antigen-presentation and immune-stimulating pathways.

The researchers even expressed antibodies produced by those EBV-infected B cells. Many of the antibodies bound nuclear antigens — molecules found in the nucleus of human cells that are frequent damage targets in lupus. In healthy controls equivalent B cells did not produce such autoantibodies.

Moreover these reprogrammed B cells could act as antigen-presenting cells to activate T helper cells. That in turn triggered activation of other B cells (even those not infected by EBV) and plasmablasts, fueling a widespread autoimmune response.

Together the evidence presents a plausible mechanism: EBV enters certain B cells, reprograms them to present self-antigens, triggers T cell help, which then amplifies antibody production and sustains chronic autoimmune attack. In other words EBV may be the spark that ignites lupus.

Experts and advocates describe the discovery as a breakthrough because it moves the field from correlation to mechanism. The long-suspected link between EBV and lupus has now been mapped at the cellular and molecular level.

The study was partly funded by Lupus Research Alliance. Their support helped make possible the detailed laboratory work that teased out how a nearly universal virus can trigger a rare and severe disease in a subset of individuals.

With this knowledge scientists can begin exploring new strategies for lupus prevention and therapy. For example they may target EBV-infected B cells for elimination. They might also explore reducing EBV reactivation or preventing infection outright if a safe and effective EBV vaccine becomes available.

While the findings are compelling, they do not yet fully explain why only some people infected with EBV develop lupus. After all, most adults worldwide carry EBV but only a small fraction ever get lupus. The new research does not yet clarify what additional factors — genetic, hormonal, environmental — determine whether EBV triggers disease. Experts note that lupus disproportionately affects women and certain ethnic groups, suggesting a complex interplay of risk factors.

Also, the study was based on blood samples, which may not fully reflect what occurs in tissues. Lupus affects many organs and immune cells from lymphoid organs or tissues might behave differently than those in circulation. More research will be needed to extend these findings beyond blood B cells and to track what happens over time.

Finally, while the mechanism makes biological sense, demonstrating that targeting EBV-infected B cells can alter disease course or prevent lupus remains a big challenge. Any such therapeutic or preventive approach will require carefully designed clinical studies.

For people living with or at risk of lupus, the results offer hope. Understanding that a common virus can cause lupus may help shift treatment away from broad immunosuppression toward more precise approaches. For instance therapies that specifically deplete EBV-infected B cells might suppress the disease without undermining the entire immune system.

On a global scale, if an EBV vaccine becomes available, vaccination might reduce not only cases of infectious mononucleosis but also incidence of lupus and possibly other autoimmune diseases linked to EBV. That would be a game changing public health outcome.

Given that lupus affects millions of people worldwide, and disproportionately impacts women and people from underrepresented ethnic groups, these findings have far reaching significance. They could help narrow health disparities by offering safer, more specific options in treating or even preventing lupus.

For decades lupus has remained a puzzling disease with no clear cause, unpredictable flare-ups, and a bewildering range of symptoms. Now a common virus that most of us carry for life may finally give meaning to that mystery.

The work by Stanford Medicine and collaborators provides strong and concrete evidence that EBV can reprogram B cells into autoimmune instigators. The discovery moves lupus research into a new era — from managing a baffling disease to targeting a root cause.

The challenge ahead will be to translate this knowledge into safe, effective therapies or vaccines that benefit patients across the world. Meanwhile researchers, clinicians, and public health actors must build on this foundation with urgency and rigor.