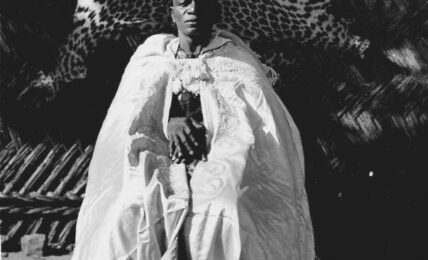

Nyadhi” – A Luo Philosophy of Self-love, Self-virtue, Achievement and Honour

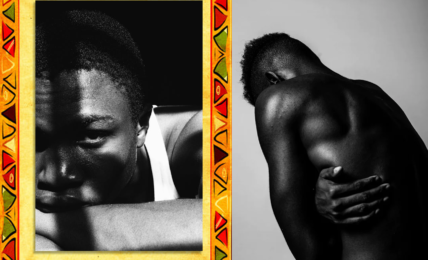

When we approach nyadhi philosophically, we find that it relates more to self-love and self-virtue. It is akin to what Aristotle called Philautia (in Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics) – “to love yourself” or “regard for one’s own happiness or advantage”. Philautia, understood as self-love, can be positive or negative/ healthy or unhealthy.