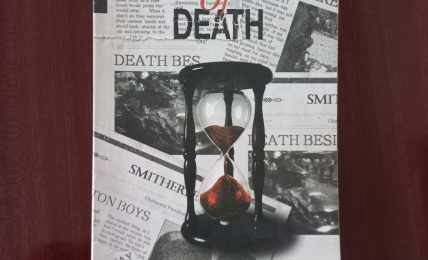

A Summer Unending

‘A Summer Unending’ follows the story of a man in a small Italian coastal village falling victim to the things he once enjoyed, sending him into a state of deep existential dread, entropy and battling what is reality and what is not.