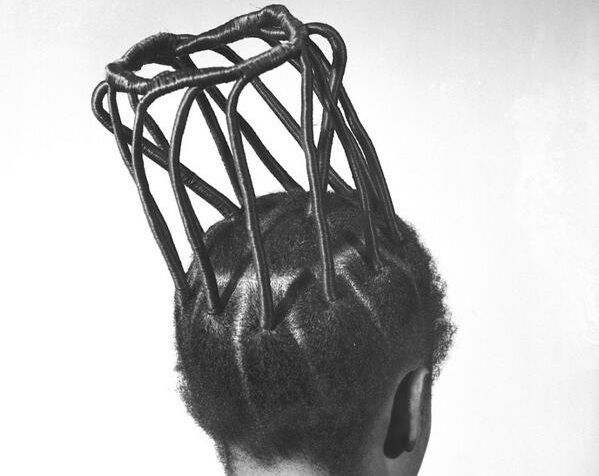

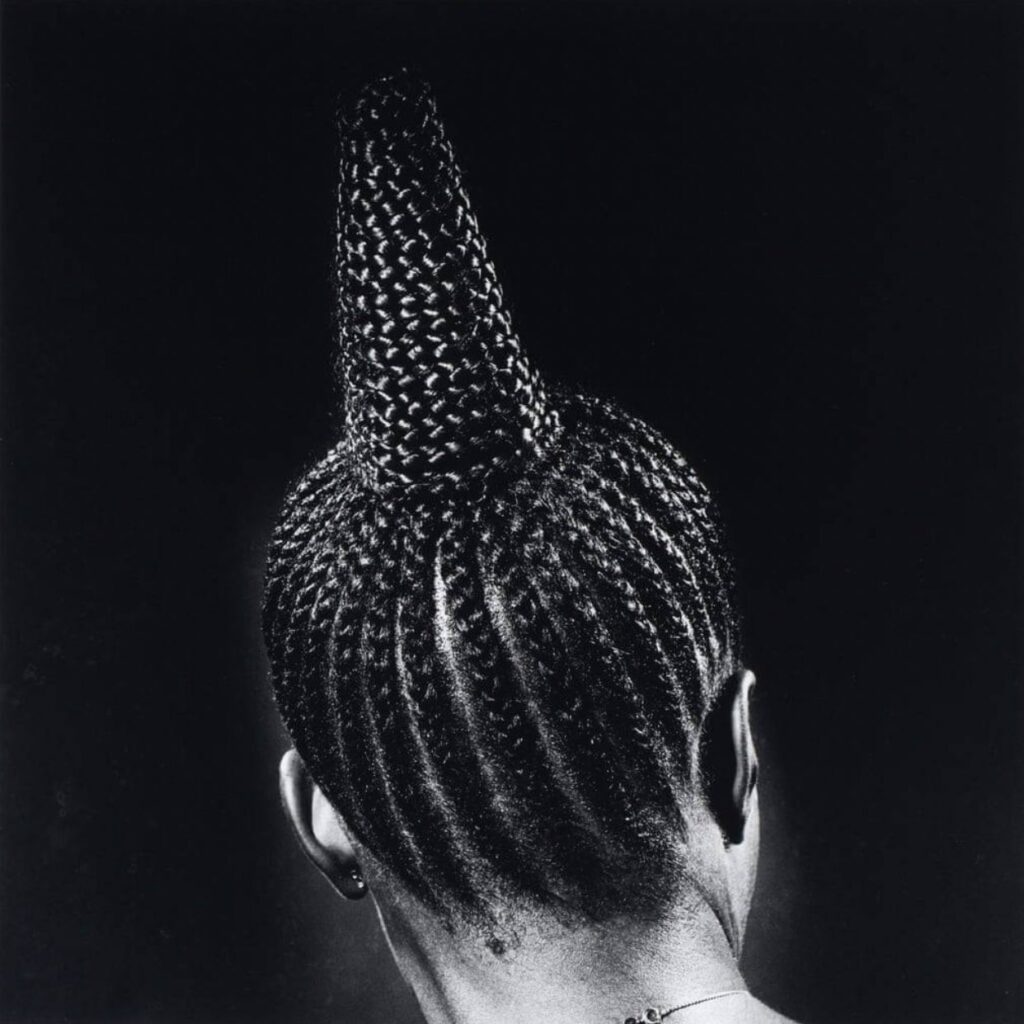

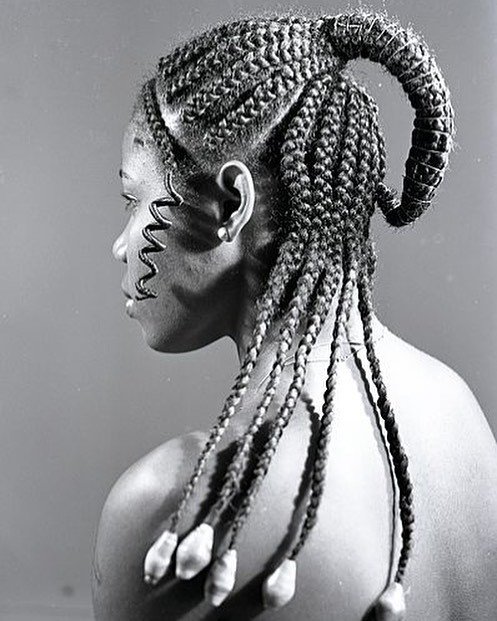

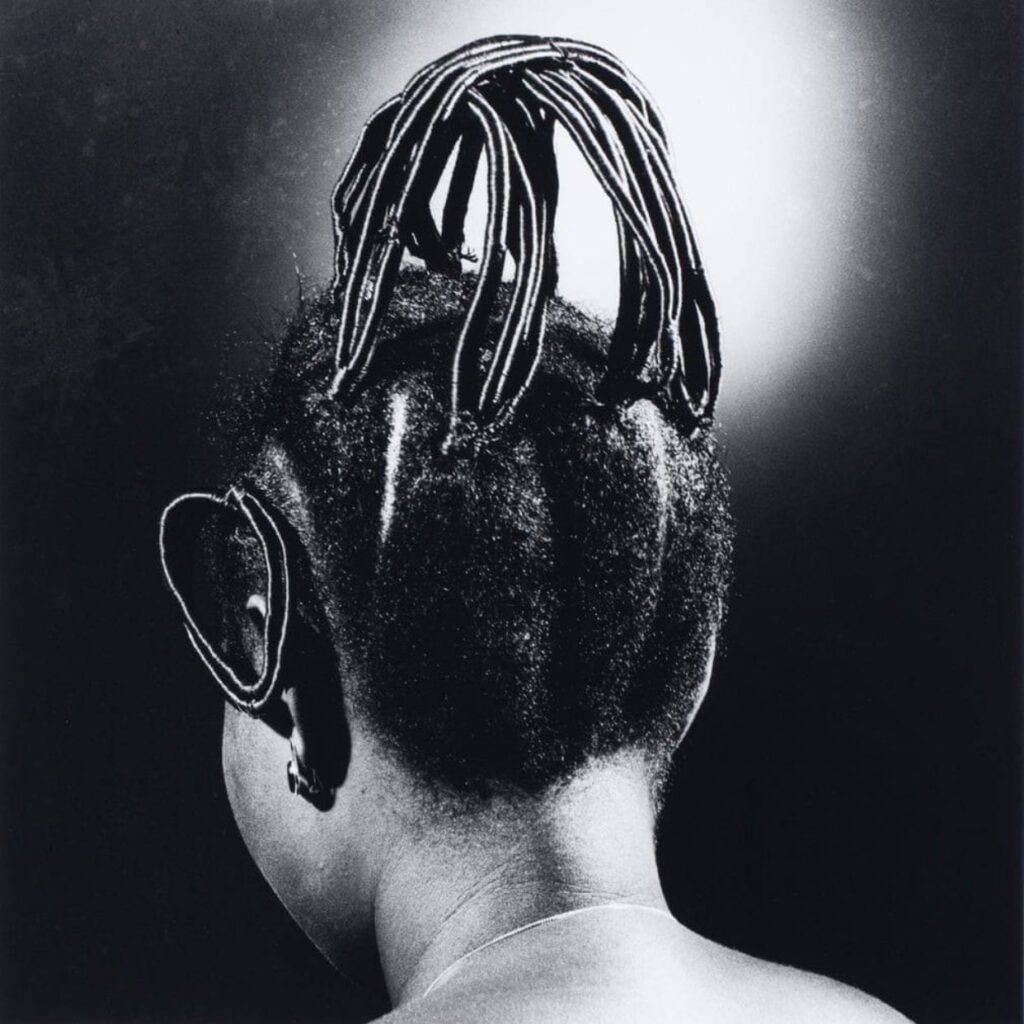

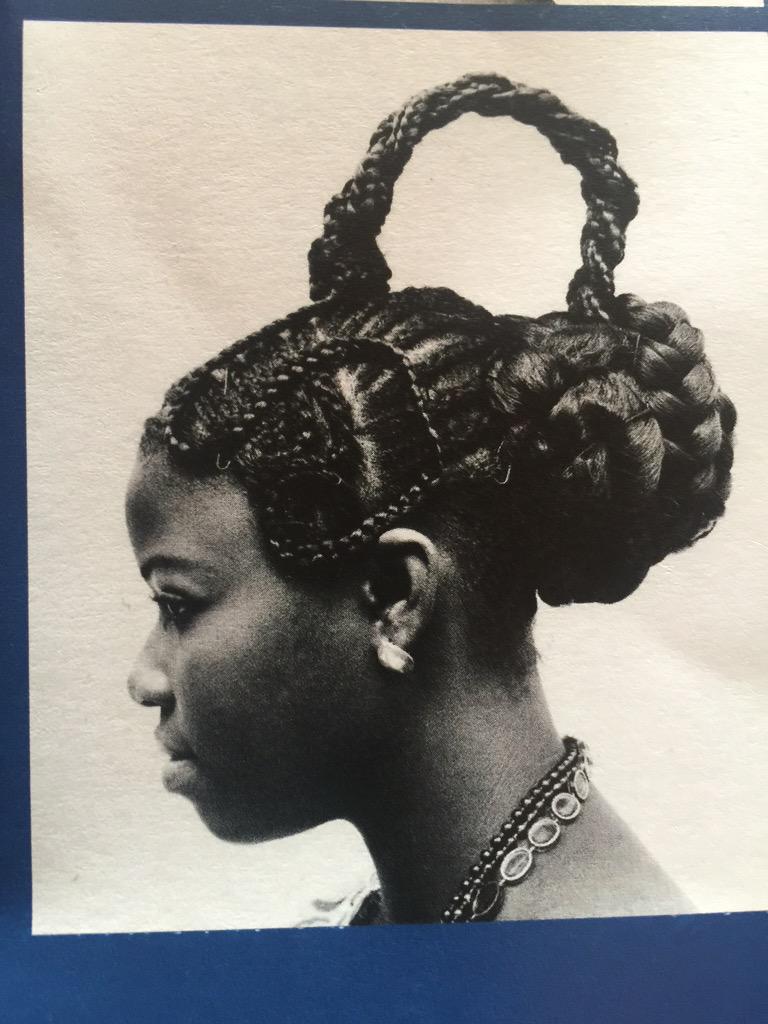

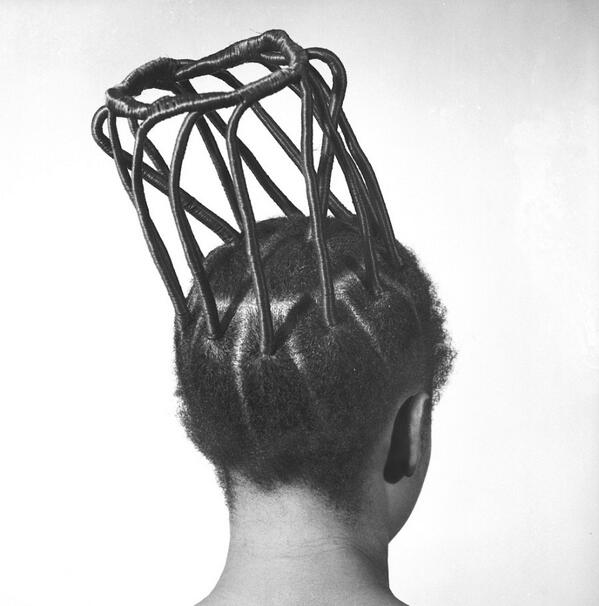

Aesthetics of African Woman’s Hair

Ojeikere's camera lens refocus the male gaze away from the female body. He makes the head the singular focus of his shots, utilizes angles and employs lighting techniques that enhance the aesthetic quality of the hairstyle.