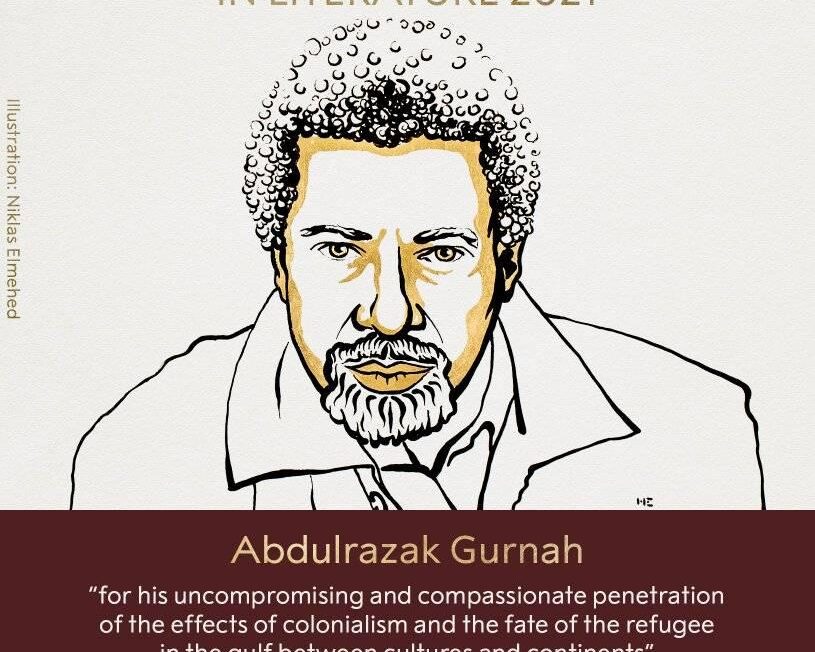

Mwende Kyalo: Abdulrazak Gurnah Deserves the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature

Abdulrazak Gurnah does not just give his readers a book to read but he bestows upon them a journey to undertake. A journey into a people whose ways of life, whose histories, are unknown to outsiders.