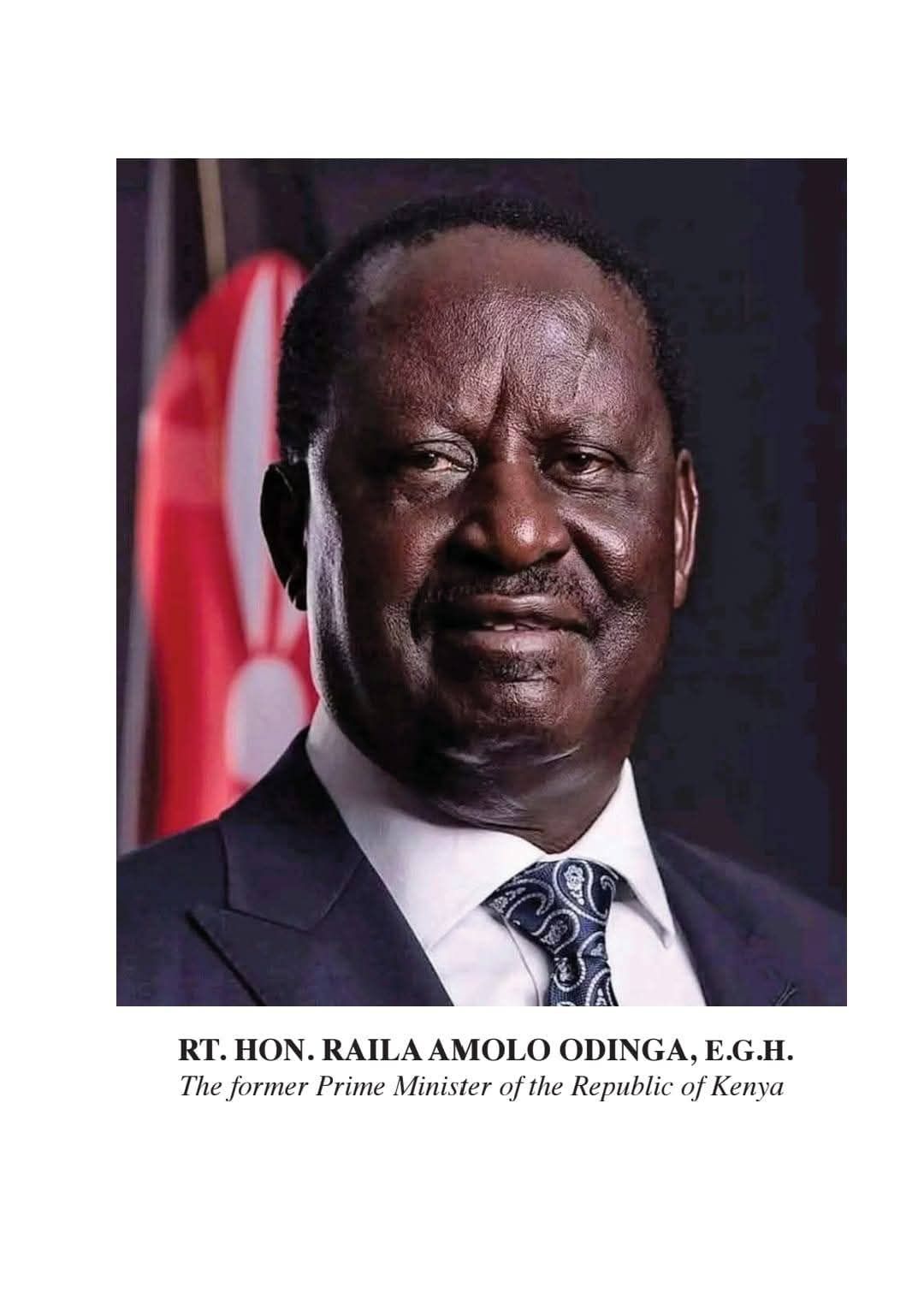

Raila Odinga: the man who changed Kenya without ever ruling it

Having self-identified as a revolutionary, Odinga later proved to be committed to institutional reform and democratisation. His greatest legacy is the 2010 constitution, which attempted to devolve power away from the “imperial presidency”, which he campaigned for over many years.