Red Gold: The Rise and Fall of West Africa’s Palm Oil Empire

Palm oil was, and remains, a key ingredient in West African cuisine, including the simple dish of boiled yam, palm oil and Kanwa salt, and Banga soup.

Palm oil was, and remains, a key ingredient in West African cuisine, including the simple dish of boiled yam, palm oil and Kanwa salt, and Banga soup.

Pauline von Hellermann, University of London

For thousands of years, the oil palm – indigenous to West Africa – has had an intimate relationship with people. An explosive expansion of oil palm groves throughout western and central Africa in the wake of a dry period around 2,500 years ago enabled human migration and agricultural development; in turn, humans facilitated oil palm propagation through seed dispersal and slash-and-burn agriculture.

Archaeological evidence shows that palm fruit and their oil already formed an integral part of West African diets 5,000 years ago.

With the exception of “royal” oil palm plantations, established in the 18th century for palm wine in the Kingdom of Dahomey, all of West Africa’s oil palms grew in wild and semi-wild groves.

Women and children collected loose fruits from the ground, while men harvested fruit bunches by climbing up to the top of the palms. The fruit was then processed into palm oil by women, through a time-consuming and labour-intensive process involving repetitively boiling and filtering the fresh fruits with water. Similar methods are still widely used throughout West Africa.

While pure red palm oil was derived from the palm fruit’s fleshy outer mesocarp, women also, often with the help of children, cracked the palm kernels to make brown, clear palm kernel oil.

Palm oil was, and remains, a key ingredient in West African cuisine, including the simple dish of boiled yam, palm oil and Kanwa salt, and Banga soup.

Throughout West Africa, palm oil was also used in soap making; today Yoruba black Dudu-Osun soap is a trademark Nigerian brand. In the Benin Kingdom, palm oil was used in street lamps and as a building material in the king’s palace walls. It also found hundreds of different ritualistic and medicinal uses, in particular as a skin ointment and a common antidote to poisons. In addition, the sap of oil palms was tapped for palm wine, and palm fronds provided material for roof thatching and brooms.

Palm oil has been known in Europe since the 15th century. It was Liverpool and Bristol slave traders who, in the early 19th century, began larger-scale imports. They were familiar with its multiple uses in West Africa and had already been buying it regularly as food for slaves being shipped to the Americas.

With the abolition of the slave trade to the Americas in 1807, British West Africa traders turned to European markets and natural resources as commodities, in particular palm oil. At the time, the main sources of fats and oils in northern Europe were animal-based – such as lard or fish oils -– products for which it could be a challenge to secure regular supplies. There was a ready market for palm oil.

Palm oil was used as an industrial lubricant, in tin-plate production, street-lighting, and as the fatty semi-solid for candle making and soap production. Breakthroughs in chemistry, in the 1820s facilitated a change to large-scale, industrial soap production.

Ever larger quantities of palm oil – increasing from 157 metric tonnes per year in the late 1790s to 32,480 tonnes by the early 1850s – were brought to the UK by small-scale West African traders.

The trade was not for the faint-hearted. Once a year, traders would spend up to six weeks travelling in small schooners to one of the many trading stations on the West African coast. There were several dozen trading stations in the Oil Rivers area of today’s Niger Delta -– the heartland of the West African palm oil trade.

European traders lived and traded entirely on abandoned sailing ships. This was partly to try and avoid deadly diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever, but also because local authorities didn’t let them build on land. Inland trade was controlled tightly by local brokers and village chiefs.

European traders gave these brokers European goods such as cooking utensils, salt and cloth. Then the traders waited on board their ships for them to return, sometimes for months at a time. Many of the African brokers were themselves former slave traders. The slave trade in the Niger Delta did not immediately stop with abolition but continued alongside the palm trade until the 1840s. Palm brokers and European traders continued to use the same network and system developed for the slave trade.

While waiting, the European traders’ coopers would assemble large casks to hold palm oil.

It was largely West Africa’s existing wild and semi-wild groves that furnished European demand. In the hinterland of the Oil Rivers and many other areas, there was an abundance of wild oil palm that could be harvested. Some planting did take place; the Krobo in southeastern Ghana, where fewer oil palms were growing naturally, began systematic cultivation in response to European demand.

In Dahomey, too, more plantations were set up. Some parts of southeastern Nigeria focused so much on the production of palm oil that they became completely reliant on yam imports from further north. However, there was no large-scale, radical transformation in land management, ownership or ecology.

West African producers successfully responded to growing European palm oil demand through the modification and expansion of existing small-scale production methods.

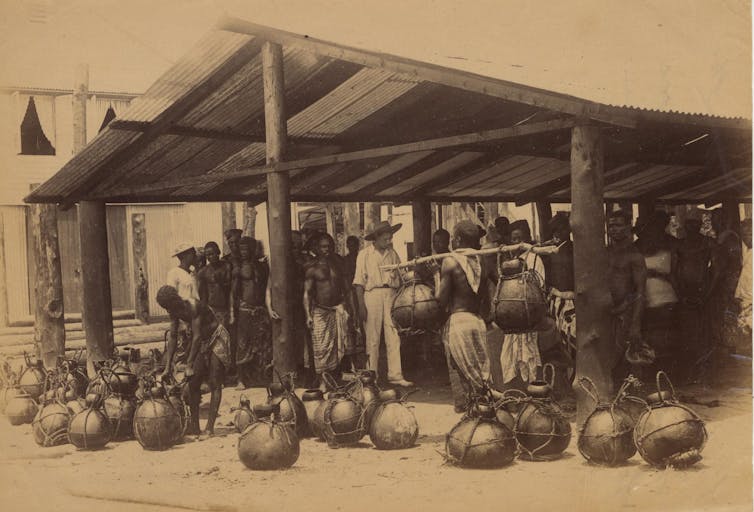

Young men did the dangerous work of harvesting fresh fruit bunches. In palm oil processing another, far less labour-intensive method, developed. Fresh fruit was left to ferment and then stamped on in large pits dug in the ground, or sometimes in old canoes. The resulting oil was much dirtier and inedible. It also fetched lower prices, but the new technique enabled much larger-scale production than before.

There was plenty of work in transporting palm oil, carrying calabashes filled with oil along forest paths to the nearest river and working on canoes. This brought some cash income for young men, but it was generally older, already wealthier men, and in particular chiefs, who were able to profit most from “red gold”, through the labour of their wives and slaves and from control of trade.

It was through brokerage that most wealth and power could be gained, and local power structures were deeply enmeshed with trade in palm oil. A particularly powerful broker at this time was William Dappa Pepple, the amanyanabo (king) of Bonny (in today’s southeastern Nigeria) from 1837 to 1854.

In the late 19th century, chemists discovered that hydrogenation could be used to process vegetable oils into margarine. Margarine played an increasingly important role in supplying fats for the diet of Europe’s growing urban working class. While the volume of imports of West African palm oil into the UK levelled off between the 1850s and 1890s, large-scale production of this new edible product stimulated renewed demand for palm oil in the early 20th century.

Between 1854 and 1874, France and Britain had already started to create formal European colonies in Senegal, in Lagos, and in the Gold Coast. British West Africa eventually included Sierra Leone, the Gambia,the Gold Coast, and Nigeria (with the British Cameroons).

In the 1930s, British West Africa exported around 500,000 tonnes of palm produce annually. Palm produce continued to play a significant role in West African rural economies, but local control of the trade eroded under colonial administration; the opportunities for wealth and power palm oil had offered local people were no longer available.

Moreover, as the colonial powers continued expanding their reach elsewhere in the tropics, a game-changing development was slowly beginning: the rise of the oil palm plantation.

Within a few short decades, expanses of Southeast Asian forest had been cleared, creating a fast track to industrial-scale monoculture plantations, thus ending West Africa’s position as the global hub of palm oil production.

A version of this piece was originally published on China Dialogue

Pauline von Hellermann, Senior Lecturer, Anthropology, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.