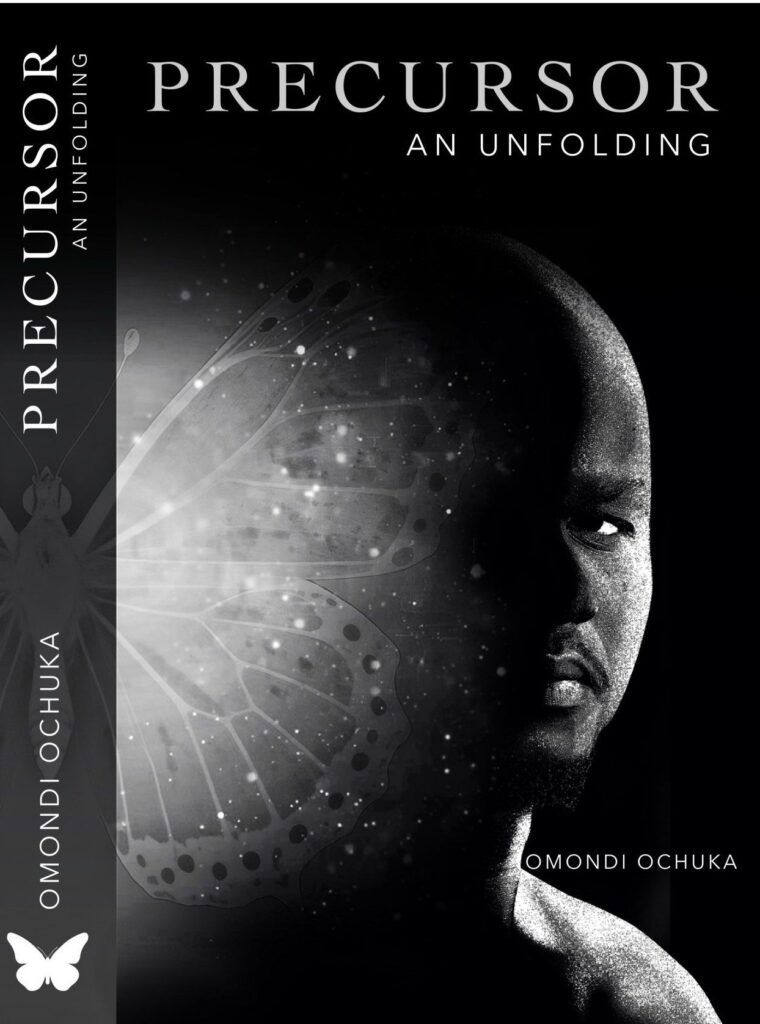

Taking My Book, “Precursor”, to My Grandmother

My book sits wrapped in brown paper on my lap. Precursor. Six years of composition while dana’s mind performed its cartridge of forgetting. Now it exists bound, physical and bearing her name in the dedication. I spent the night touching the cover, feeling sick with accomplishment and loss, that particular nausea of creating something permanent while watching someone become provisional. Even before the city’s humidity thickens at the edges of the lake, the nights behind me stack themselves into brittle plates. Nights of drafting and tearing, revising, arguing with ghosts, wondering whether memory is a rope or a river. I bring all that restlessness into this homecoming. I am gut-full with joy-grief and the double-edged brightness of knowing she will finally hold what I’ve spent years breathing toward.