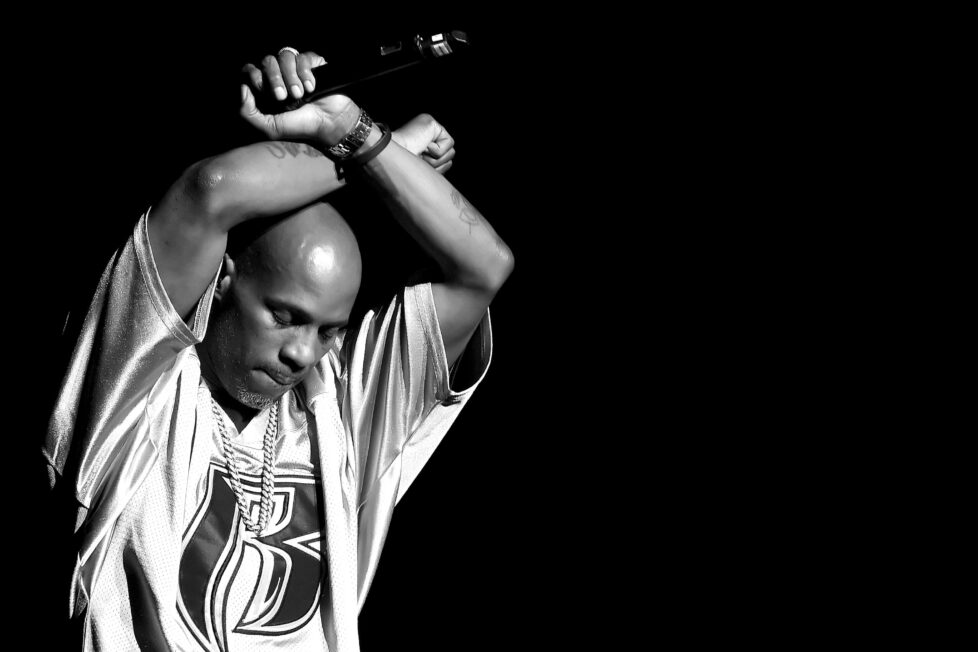

DMX, A Rap Legend, Dies at 50

In 1998 DMX released two albums in the same calendar year — both debuting at No.1 on the Billboard 2000, marking the start of a two-decade iconic career beset by struggles with drug addiction, legal troubles, and family troubles.