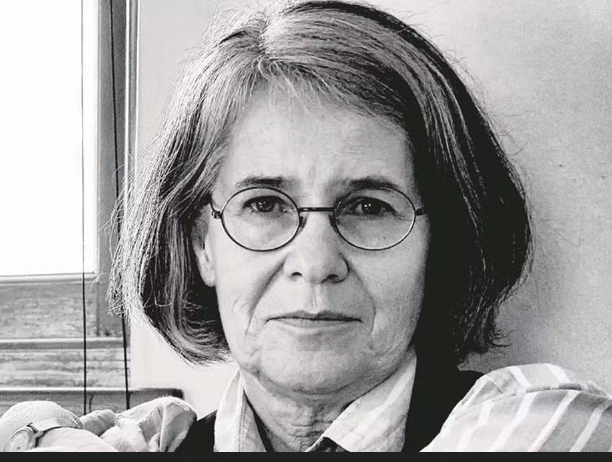

Antjie Krog and the role of the poet in South Africa’s public life

This year Antjie Krog turns 70 and her passions and commitments, forged in the 1970s, show no waning. For decades she has represented the important role that a poet can play in public life in a fractured country.