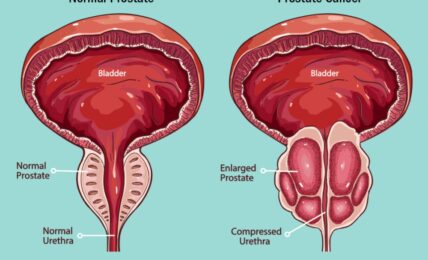

Culturally Sanctioned Silence on Male Infertility

Even though males are solely responsible for 20-30 percent of all infertility cases and contribute to 50 percent of cases overall, infertility is still viewed as a woman’s burden, while male infertility remains invisible, enjoying socially sanctioned silence to avoid upsetting hegemonic masculinity.