How Kenneth Kaunda made Zambia a ‘Christian’ Nation

Singing 'Tiyende pamodzi' conjures up in the Christian imagination, ideas of finding ‘the way’, ‘journeying’ and being on a ‘pilgrimage’.

Singing 'Tiyende pamodzi' conjures up in the Christian imagination, ideas of finding ‘the way’, ‘journeying’ and being on a ‘pilgrimage’.

Tiyende pamodzi ndi m’tima umo; Tiloke Zambezi ndi m’tima umo; Tiloke Limpopo ndi m’tima umo; A youth tiye, amai tiye, atate tiye; Tili pamodzi ndi m’tima umo

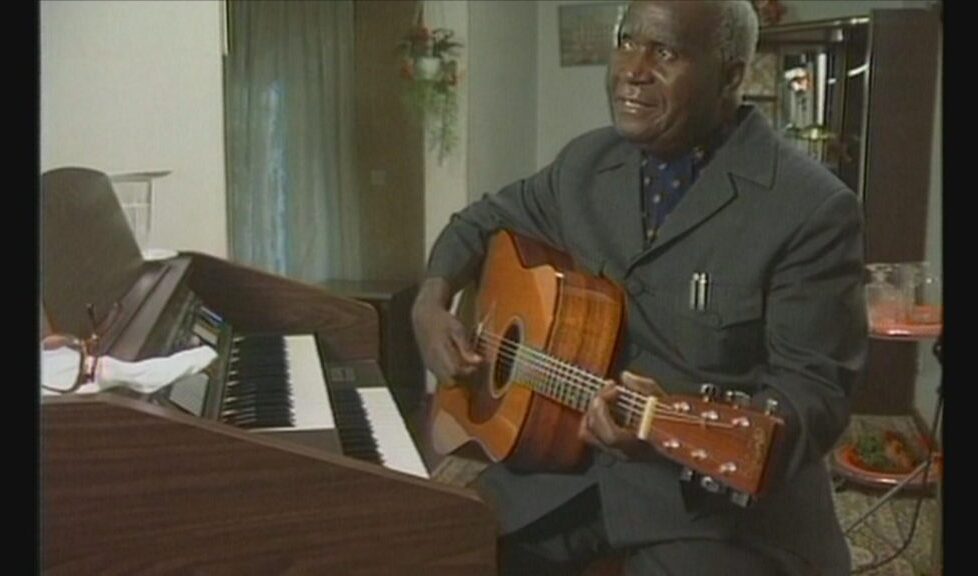

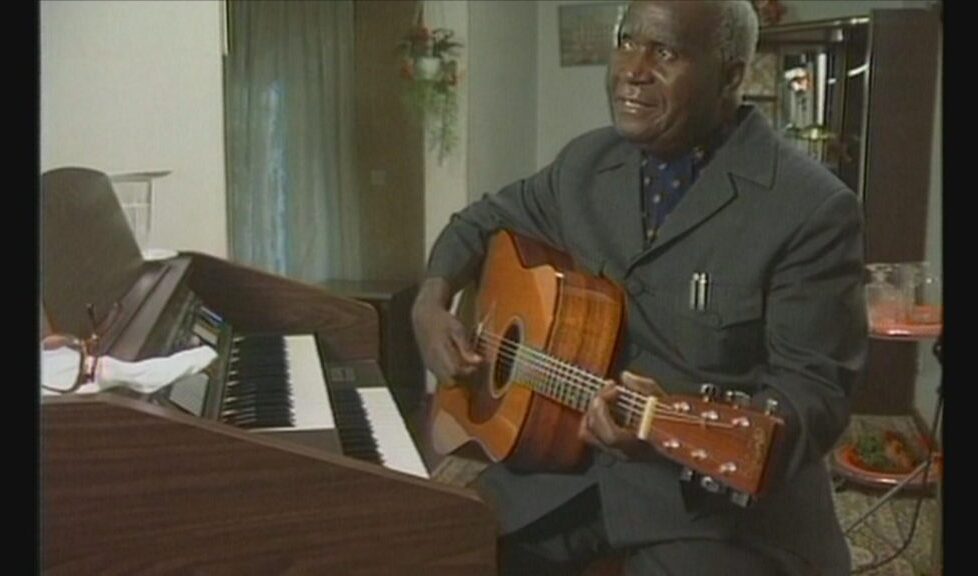

Tiyende pamodzi (let us go/walk together) is a call-response liberation song Kenneth Kaunda (aka KK) would break into anytime, anywhere — during church service, a political rally, a diplomatic event and in the parking area. Together with his rallying call, ‘one Zambia, one nation’ now enshrined in the Zambian coat of arms, tiyende pamodzi sums up his entire political vision and ethos.

Kaunda’s political vision was so pervasive. It found expression in the religious sphere when KK became signatory to the formal document that sealed the union of several missionary-founded churches to became one entity, the United Church of Zambia (UCZ). ‘One Zambia, One Church’ became the religious version of the Kaunda political slogan.

It was, as Mwangala Raymon wrote, an expression of ‘the desire to break free from the colonial past and to create a national identity cantered on values which he considered true to the African heritage and to his Christian background’. Zambian humanism ‘applied to all spheres of public life during Kaunda’s reign as president. Kaunda intended it to provide the moral basis for all human activity in the country, political, economic and social. In a sense the ideology was meant to be the social cement that held together and inspired the nation.’

Singing Tiyende pamodzi conjures up in the Christian imagination, ideas of finding ‘the way’, ‘journeying’ and being on a ‘pilgrimage’. Walking together echoes in Kaunda’s ideology. bUt what were these new ways of walking together, of being together? In what ways did they challenge the racial discrimination Kaunda experienced growing at Lubwa mission and later as a liberation struggle icon.

In a personal interview[1] I did with KK in May 2009, he narrates several anecdotes about the divide he saw between the living conditions of white missionaries and that of his own black missionary family. He tells of the segregated seating in the sanctuary during Sunday worship, including an incident when he confronted one of the missionary wives for mistreating his mother and sister while attending a women’s activity in the church as Lubwa.

Through Tiyende pamodzi, KK’s reaffirmed his personal faith, Christian ideals and African values that would play an important role in the struggle and nation-building. In his own words, ‘more things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of’. He sowed the seed that would position religion and the church at the centre of Zambian politics.

So if you want to know who made the ‘Christian nation” that Zambia has become both famous and infamous for, forget about the born-again trade unionist called Frederick Chiluba — it all started in the Kaunda era. His upbringing, education and the nature of his presidency shaped a political vision enshrined in Presbyterian Christianity, as was his philosophy of Zambian humanism. Therein lie the roots of notions of a priestly president and a compliant church throughout the Kaunda presidency. Even though KK did not declare a Christian nation, he laid the foundation for the declaration.

Kaunda had devised a complex system of patronage over the church that served his political ends. He was a life-long member of St. Paul’s congregation of the United Church of Zambia and served as a lay preacher. I recall while residing at Kenneth Kaunda Secondary School in the late 70s and early 80s, on at least two occasions, KK was home at Shambalakale farm – his personal residence in Chinsali — and he preached during the Christmas service at Lubwa UCZ congregation.

Ironically, Alice Lenshina, former leader of the Lumpa church, whom the government incarcerated, banned her church and later placed her on life-long house arrest, was a member of the same congregation. I asked KK, during the interview, about his dealing with Lenshina. Kaunda declined to answer and simply stated, ‘I was not responsible for the Lenshina massacre, I was Prime Minister at the time it happened.” State violence towards the Lumpa church exposed the underbelly of Kaunda’s shrewd politics.

An exploration of KK’s spirituality, therefore, provides a key for understanding the competing narratives about the significance and problematic aspects of the declaration of Zambia as a Christian nation. The distortions in church-state relations and the self-understanding of the Church in Zambia today are an enduring legacy of Kaunda. Understanding the long shadow Kaunda’s vision of nationhood casts on Zambia is important for the country to move forward.

There is need to probe the contradictions that arise from subsuming the constitutional functions of the presidency to God. Political expediency lies beneath theocratic claims inherent in the declaration of a Christian nation. The contradictions therein raise disturbing questions about conceptualisation and performance of power Zambian political life.

Chiluba made the declaration of a Christian nation in 1991, by which time the Zambian social reality of enmeshing and subsuming political, economic, social and spiritual power under the presidency had already taken root. Zambia therefore serves as a case study for a critical assessment of the rise of Charismatic Christianity in Africa, its shortcomings, exciting possibilities and world-view-shaping potentials. [2]

***

Kuzipa Nalwamba is a staff member of the World Council of Churches (WCC), serving as lecturer at Bossey Ecumenical Institute and as programme executive for Ecumenical Theological Education (ETE). She is a retired ordained minister of the United Church of Zambia (UCZ).

Tinyiko Maluleke is a senior research fellow at the University of Pretoria Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship.

[1] Kaunda, Kenneth. Interview with Kuzipa Nalwamba. Personal Interview. Lusaka, May 21, 2009.

[2] See Tinyiko Maluleke’s foreword titled, ‘Of Priestly Presidents and Christian Nations’ in Chammah Kaunda, 2019. The Nation That Fears God Prospers: A Critique of Zambian Pentecostal Theopolitical Imaginations, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, vii-x.