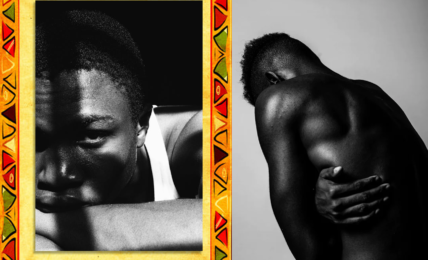

Octopizzo: An Ever-Present Force in Kenya’s Hip Hop Culture

In my mind, Octopizzo was like Lex Luther, but in the rap world. Or like Fifty Cent, who is the biggest villain in the US rap scene. In contrast, I saw Khaligraph as the hero, the kid who survives in the world through grit, guts, and wits.

I agree. For a long time, I’ve felt people focused too much on Octo’s pen skills without paying too much attention to his sound. As you say it, his sound is timeless, unique, and you can tell it will get better with time. I can only wish him well. Let’s see what the future holds. Great read.