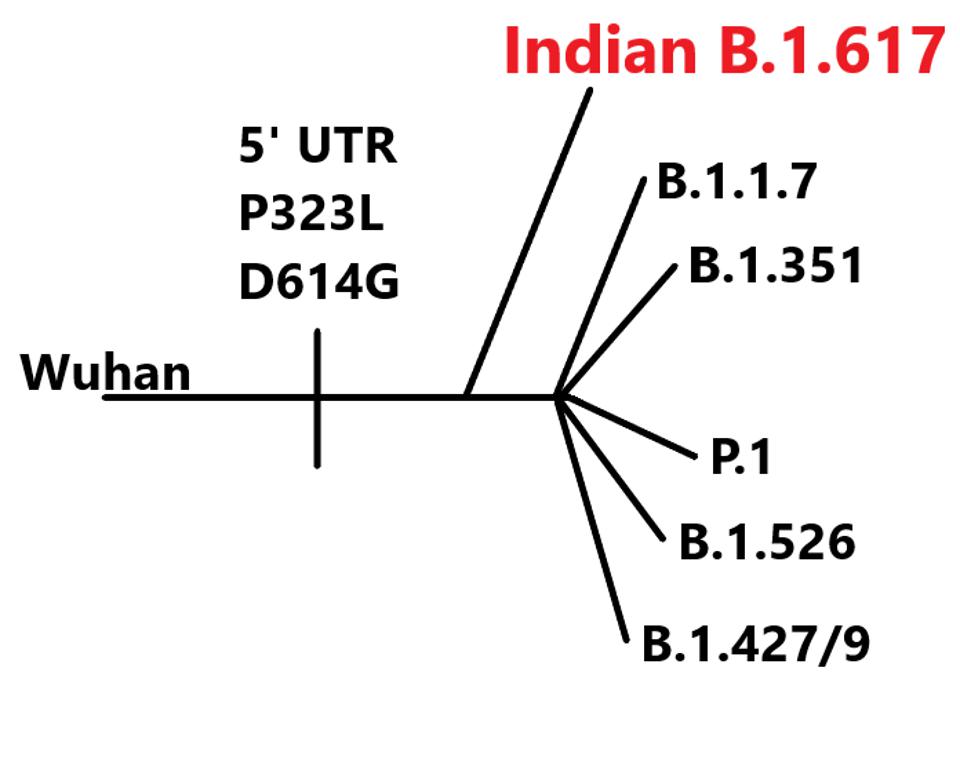

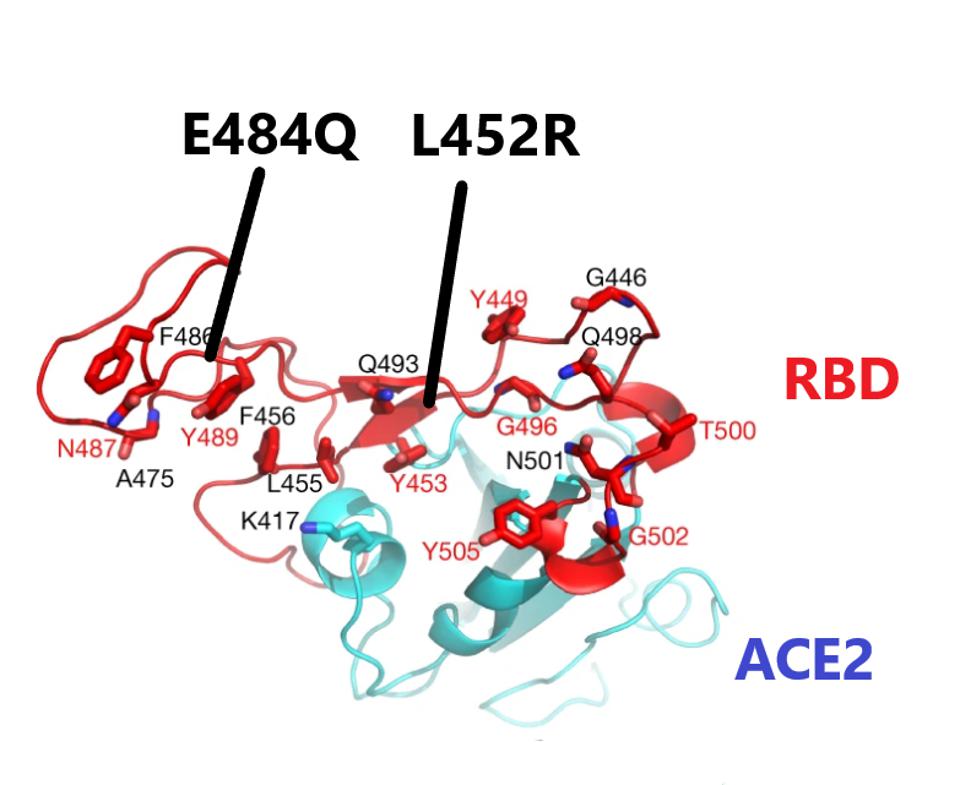

The Double Mutant COVID-19 Variant from India Detected in Africa

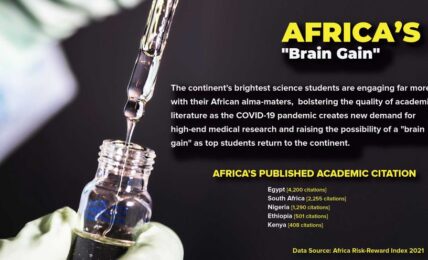

Even though COVID-19 infections and fatalities remain comparatively low, African governments have struggled over the past year to expand healthcare capacity and meet vaccination targets. The continent has a fragile health ecosystem and cannot cope with the virulence of the double mutant currently devastating India.