The Safari

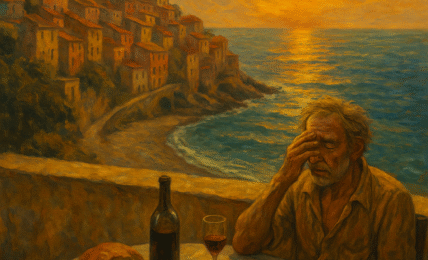

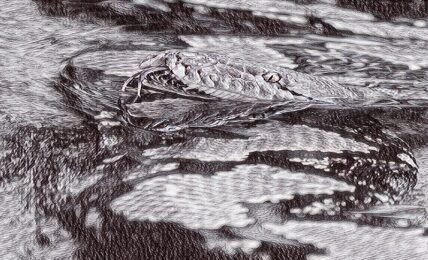

Three childhood friends — Aasir, Sira and Adira — embark on a Safari, to climb to the peaks of Oldoinyo Oibor and conquer the torments of the wandering waters of Mto Mkuu, as initiation for selecting the Chosen Ones: the Enlightened Elders of Songhai. Of every thousand who embark on the Safari, less than five ever return. And for almost all of them, their bodies are never recovered, and empty coffins are buried by their people instead. Only those who can choose to die are ready to know the truth. They must confront the tragic and bizarre consequences of their bravery.