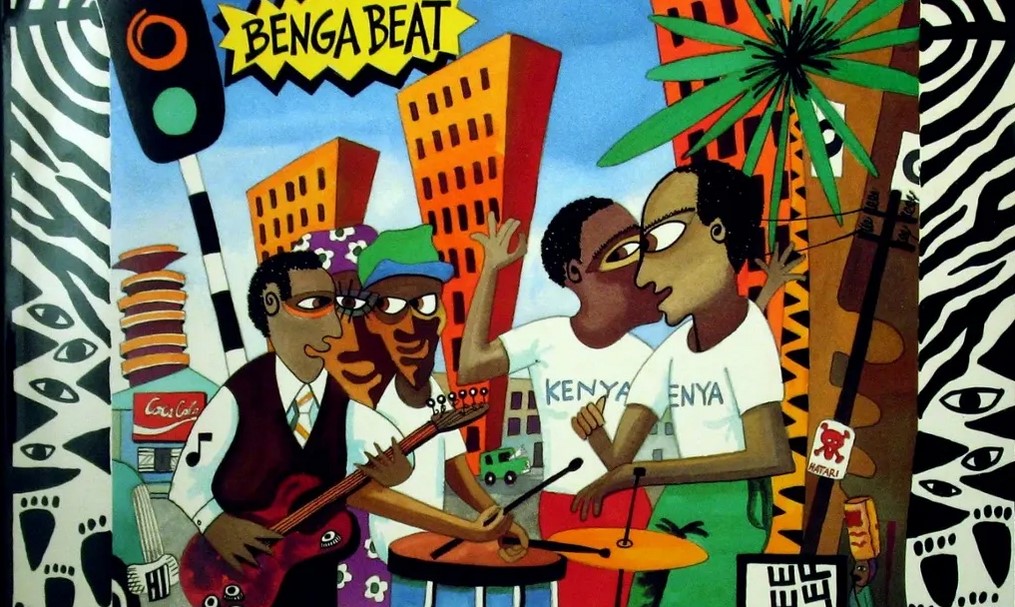

Benga’s Journey from East Africa, to Zimbabwe, and the Dance Floors of Colombia

Benga arrived in Colombia after Osman Torregrosa, a businessman of picó dances in Barranquilla who, looking for music, had gone to Aruba and Bonaire, then Martinique, Suriname, New York and Paris to look for music that would cause a sensation, for a sound that was modern and traditional at the same time. In Colombia, Benga is known as ‘música rastrillo’.