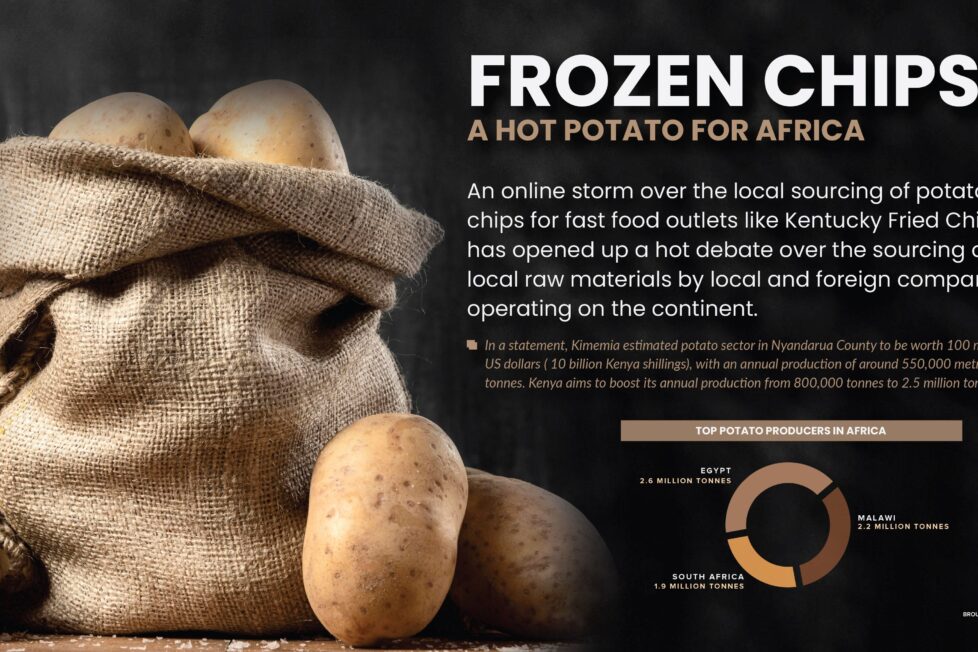

Frozen Chips: A Hot Potato for Africa

An online storm over the local sourcing of potato chips for fast food outlets like Kentucky Fried Chicken has opened up a hot debate over the sourcing of local raw materials by local and foreign companies operating on the continent.