Historical Snapshots — Chief of the Chip Tribe, 1947

Humans will always want to see, want to understand the past, and the only way to do so will be through the creations of those in-the-now who have a mind out for those to come.

Humans will always want to see, want to understand the past, and the only way to do so will be through the creations of those in-the-now who have a mind out for those to come.

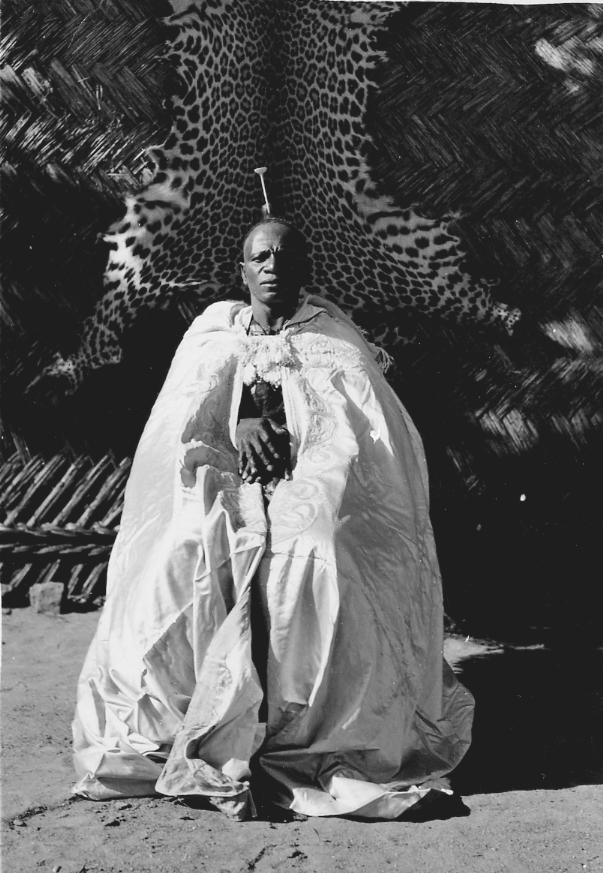

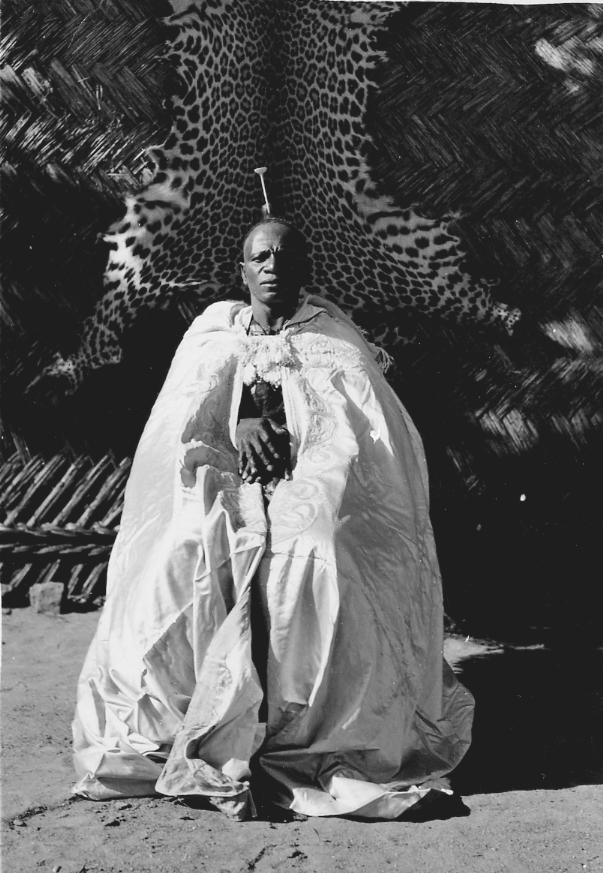

I first saw the photograph in the Nigeria Nostalgia Project Facebook group. A middle-aged man sitting on a stool, his body wrapped in white cloth, his hands peeking out, just above his stomach, resting on an invisible staff. The chiaroscuro has blanked out half his face but what stares at the viewer is utterly inscrutable, a man of command, a forehead furrowed lightly in concentration. Beyond the man, are two things — an ivory hairpin at the back of his head and the stretched-out skin of a leopard. The word that came to me, then as now, is — regal.

The search for context led me to the digital archive of the British Museum, to an image given the registration number Af, A57.130, and asset number 50221001. The description reads:

Nigeria, frontal full-length portrait of seated adult male “chief”. Wearing robe, hair-ornament. Leopard skin hung on woven reed wall in backgrounds.

A further note, taken from a typed list accompanying the image, yields —”Tribes of the Plateau (Pankshin Division.) Chief of the Chip Tribe. Note the Tsafi Fwan in his hair”.

The note was made by the photographer, British-born South African, Dr. Joseph Denfield (1911—1967). Denfield was a medical doctor who enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1942. His wartime adventure in Nigeria was, apparently, taking photographs. He moved back to London in 1947 and gifted this image, alongside 136 others, to the British Museum that year.

In the period since the image was taken, the spelling of the name of the ethnic group has shifted to “Miship”.

Today, the Miship occupy 33 villages in Plateau State in central Nigeria. My hometown, Jos, is the capital of Plateau State. Tsafi is the Hausa word for sorcery, indicating the chief was of a pagan persuasion. Fwan seems to be the word for God, seen as a prefix in many names from the area, names such as Fwanshishak and Fwangchi. Traditionally sedentary farmers, their paramount chief is titled the Ndaalong Miship, and the ethnic headquarters is at Kwala.

The word “tribe” is, of course, a no-no as a result of its undoubted pejorative tone and the heavy colonial gaze which sees, as perhaps Denfield did, Africans as Others markedly different from the civilized eye on the other end of the lens. The language of the Miship people is in the Afro Asiatic family tree and the roots of the people lie elsewhere, in Kanem Bornu, and the wider Sudan. It shares roots with Bolewa and Ngas, which have oral traditions of migrations from Kordofan.

Another description adds that it was “one of four prints mounted on album page.” The others were:

Small group of adult females and a child, sitting on ground outdoors. Wearing personal-ornaments including disc-shaped lip-plugs and ear-plugs, bowl-shaped hair-styles. Two females dressing hair of other two females, using small pointed tools. Female at right holding young child.

This note piqued my interest further. I wanted to see the other images to help piece together the sociocultural context of this small ethnic group in the middle of the last century. The lasting importance of the work of Denfield must lie in these images of traditional societies on the verge of being lost. I recognize immediately that only a high degree of culture and rootedness can produce the ivory comb on the head of the chief, just as I believe women’s coiffure is always very eloquent about the aesthetics of people. I sought the image of the child, particularly, from a hunger for the clues the upbringing of children reveals about societies past.

My effort failed. If those images still exist, the British Museum, in its current role as general curator, have neither assigned an “asset number” to them nor uploaded them on their website. Thus I, closer to these ancestors than any curatorial function, am denied access. It is a stunning state of affairs that if I really want to see those images—for research or any purpose—I would need to apply for a British visa, pay for a flight ticket, pay for a London hotel and living costs, pay admission fees to the British Museum, all in order to see these images of my own people. There is no doubt that my heritage is an asset, the question is to what extent it is still mine.

Perhaps something may be said about this in this period of loud demands for the repatriation looted art centred, but not limited, to the Benin Bronzes stolen by British soldiers in 1897. The question of the colonial acquisition of African art and artefacts now held in museums and private collections underlines the inequity and inequality of the power relations within which this chief, and the Miship people, were caught ever since Lord Lugard’s guns fell silent in the 1910s. However, I remind myself that these particular images were not in fact stolen, even as my painful lack of access remains. If it were not for Denfield, we would not have these images. Had Denfield not gifted his images to the British Museum, I would never have met this Chief of the Miship in a Facebook group, and there would be no basis for the present writing.

No matter what is said about the colonial gaze, the truth is that without the personal passion of a Joseph Denfield, we would not have this citation. Further, and ironically, the relationship between the coloniser and the colonised is not always a straight-forward one of pillage of one by the other. In this case, something necessary and important remains, the documentation of lives that would otherwise be lost, which monument, now digitized, gives a nod to existence in a different time.

Whatever it is, we are left with an image of a man of his times in his prime, wondering, perhaps, what we are all about. The lasting lesson of the Chief of Miship is this: that his photo, taken amongst others by a British adventurer who happened to have a passion for photography, is now an asset that can inspire conversation.

The challenge, of course, is for today’s descendants of the people that Denfield captured so powerfully to view the documentation of the present day with deliberation and seriousness, with passion even. It is true that the medium of collection and re-collection has changed, from Kodak film to digital pixels for example. It is also likely that something is lost in the modern reflex for editing images, such that definitive analysis is always exceedingly treacherous terrain. I think though that humans will always want to see, want to understand the past, and the only way to do so will be through the creations of those in-the-now who have a mind out for those to come.

11 Comments

This is so interesting! I will try to confirm this King from historical documents of the Mhiship people that I’m part of. Thank you for bringing this to our knowledge.

Thank you very much, Mark. Please write about the identity of this particular chief. I’m curious to read your research and I’m sure Sisi Afrika would be a great place to publish your findings too.

You have done a great job for the Miship nation. This has given us a sense of direction in the history of Miship people especially students of history and and anthropology. It will also open the door for studies in the economic and political activities of the people. You earn my academic respect for this short exposition. Thank you respectfully.

Thank you very much, Dakwam. I’m glad that my essay has sparked interest in the people of Miship. I hope there will be more effort to document this history, as well as the histories of related people in southern Plateau. Thank you once again.

This picture of my paramount Chief of 1947, is absolutely gorgeous to the Mhiship ethnis group & students of history. We will be grateful to read if there are additional pictures or literature please.

My pleasure entirely, Aaron. It has been a pleasant surprise to read all the feedback to my short essay. I hope to do more research in southern Plateau and will definitely share what I learn. Warm regards.

This is very inspiring and captivating. Thank you for the rich research which has opened and increased my knowledge and perspective on the History of the Chief/ King of my dielect and tribe, Mhiship in Chip. Incidentally I’m from kwalah.

I must commend you for this write up. You actually did a good job and great sacrifice to get this work become a reality. I will appreciate more information when available.

Thank you,

Tongnaan.

Thank you very much, Tongnaan, for your note. I appreciate your taking time to give feedback. History is a pet pleasure of mine and now that there has been some interest in this, I hope to put in more effort on the histories of the peoples of southern Plateau in the coming months. Warm regards and thank you very much.

Quiet interesting. We may have more hidden historical compendium in some Libraries across the globe.

Wow! This brings to mind a powerful coronation proceeding ceremony I witnessed in Kwallah as a child, and the blacksmithing cottage I also saw in Mhe’es-Jibam at the time. We lost all of them ignominiously over a short period of time because of our uncontrolled appetites for exotic things that have now paralyzed us completely. I mean, like the Japanese, Chinese, etc, our ingenuity, creativity and innovation, adaptiveness, identity, and industry – and not the Light, of course.

Thank you for unearthing this challenge, Richard. It is a challenge to our generation: now literate and set to explore and restore the glory of the illustrious small ethnic entities that uniquely populate the southern escarpment of the Jos Plateau.

Thank you, Richard.

I find this fascinating!

A great discovery, indeed; and a truly fascinating one at that. Well, objectively, I’m not from the Southern Plateau in the context of ongoing conversations here. I’m of the Kantana tribe found in presentday Farin Ruwa Development Area, Wamba LGA, of Nasarawa State. You may recall that the area formed part of what used to be Akwanga Division of Plateau Province. My interest is that several photographers and/or adventures had frequented Kwarra, my hometown, the capital of the Kantana tribe and organized many photography sessions among other cultural activities; recorded on vinyl and taken away with no tracks. Fact now is no record of such assets is available with the community; and, so, could well be stucked in some obscure corner of some European museums, as well. How could you be of help in providing a lead to uncover whereabouts of such assets? Thanks and praying for more grease to your elbows!