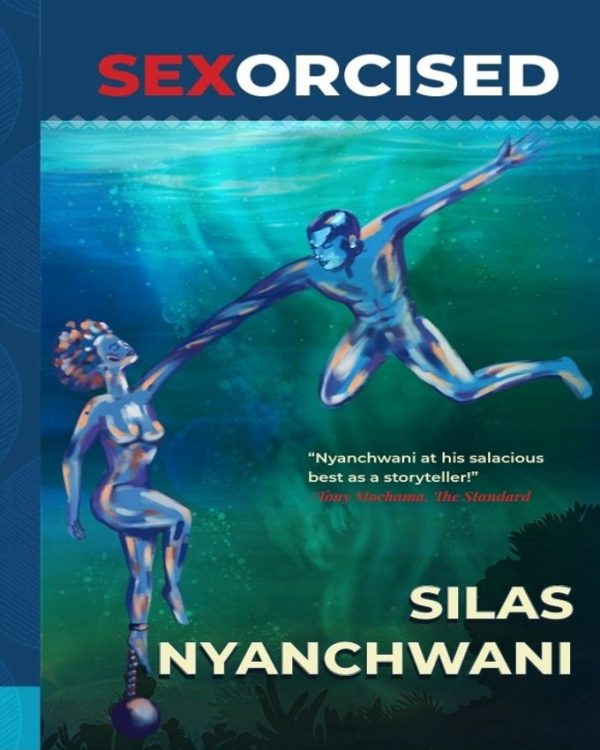

The Growing Pains of Modern Marriage in Nyachwani’s “Sexorcised”

“Sexorcised” is the story about Bruce Momanyi, a man of enviable social status, married to Lucy, an equally gifted woman, with a fast-rising career.

“Sexorcised” is the story about Bruce Momanyi, a man of enviable social status, married to Lucy, an equally gifted woman, with a fast-rising career.

If Silas Nyachwani’s debut novel, “Sexorcised”, was a musical piece, it would obviously fall in the category of techno, because of how fast the narrative flows, and the upbeat nature of the characters, who despite their flawed existence, continue to confront life with dogged vitality and resilience. The opening paragraph captures the rhythm of a tantalizing tale that will, in the final analysis, force us, to ask ourselves one of the 21st century’s most controversial questions: Is marriage worth it?

It reads thus:

The first time I fucked Maureen Mwakadzi was the night after the court finalised the divorce with my wife of 13 years. It was the best sex in like five years; I lasted longer than any 41-year old man, let alone a stressed 41-year old would. That night, I did things that I last did in college and had thought were impossible in my increasingly arthritic self. It felt so good.

“Sexorcised” is the story about Bruce Momanyi, a man of enviable social status, married to Lucy, an equally gifted woman, with a fast-rising career. The couple — like other genuine middle-class Nairobi couples — as gleaned from Momanyi’s flashbacks, lived the near-perfect life, which is often punctuated by interactions with high society, raising cute children, having regular sex, and most importantly, enjoying the smalls joys and delights of a happy home. One day, however, like all nirvana, everything comes tumbling down like a pack of cards after Momanyi learns that his wife has been cheating on him. His desperate attempts to salvage his marriage drive him into utter desperation, despair, and an ever cynical view of life. He ropes in some of his old friends like Fred to make sense of his tribulations, but they are also wrestling with their own marital demons. Beaten down to a pulp by life, Momanyi contracts the services of a private investigator to help him catch Lucy in the actual act of cheating – a rather (ir)rational decision that will set in motion a chain of events that will change forever everyone implicated in the story.

Several issues stand out in the novel. First, like any genre fiction worthy of our attention today; the author offers an incisive and brutally honest commentary on moral decadence in Kenyan society with the family unit as its focal point. His argument is augmented by the familiar narrative setting of Nairobi, where studies confirm married men and women constantly cheat on their partners with reckless abandon and defiance. A study conducted by Ipsos in 2015 reached a damning verdict as reported by The Standard that “about 79 per cent of women interviewed… revealed they had or are having an affair with a married man, and that six out of every 10 married Kenyans cheat on their wives.” And yet another 2017 research commissioned by Infotrak Research and Consulting arrived at the same baffling conclusions of rampant infidelity among couples. Momanyi, despite his sometimes unreliable narration, captures the warped philosophy that fuels the cheating habit by declaring that “when a man stops fucking his woman or the woman no longer wants sex, it means there is a good deal out there” which leads us to the book’s second strength.

The author has deftly shone a spotlight on the dangers of individualism, where the obsession with satisfying one’s primal desires and fantasies, ultimately leads to broken homes and dejected men and women. The preoccupation with sex, in particular, among the characters, is a metaphor for understanding the gradual erosion of the social fabric. Sex becomes an end in itself rather than a means to an end. Nyanchwani reinforces this argument with his cheeky wordplay of ‘s-exorcised’, whereby real redemption and individual transcendence is only possible through manic sleeping with multiple partners.

But is there a way of tracing the genesis of the runaway individualism especially in urban areas such as Nairobi and Machakos where the narrative plot finds its drive? Is it even possible to attribute the individualism to the modern pressures of career where husband and wife are (in)dispensable cogs to the invisible machine of global capitalism? Again, none other than the narrator himself helps us to contextualize some of these economic tensions that inevitably clash with individual and family values. Momanyi, though a highly self-absorbed character whose remarks and comments should at times be treated with utmost caution and restraint, in retrospect, recalls “when his marriage died or started to die”. It is when “I got heavily busy [with work], and I forgot about my family.” Work essentially replaced the warmth and security of bonding with his wife and children. It is then that shit hit the fan!

The third, and I believe, the most illuminating take away from “Sexorcised” is its compelling portrayal of modern anxieties of relationships currently afflicting Kenya’s mostly millennial generation, and which is often highlighted in social media discourses. The novel poses such fundamental questions as: Is marriage really an institution of happiness and contentment? When a marriage fails to make sense for either of the partners, is divorce the answer, or the couple should seek the advice of extended family members? What happens when your wife of 13 years starts cheating with her boss, and seem remorseless? And what happens when a man neglects his wife and children for the sake of career progress and social status? While Bruce Momanyi is himself not a millennial, his social network that comprises fleeting characters like Odhis, Sharon and Shanice, is a lost generation that is frequently wrestling with demons of rejection, heartbreak blues, unreciprocated love, or the blatant exploitation of one’s partner – kukula fare – while still trying to make sense of whether marriage is important. Moreover, traditional and western values meet and clash fiercely worsening a rather fragile situation as Momanyi remarks: “I know as modern men, some of us have become wimps in the traditional sense, in the hope that we will be cool husbands and awesome fathers, as portrayed in romance novels and bad American movies.”

Like most self-published novels being churned out of the Kenyan book industry at breakneck speed, the first edition of “Sexorcised” suffers the all too familiar weaknesses of offending typographical errors and the occasional grammatical eyesores that keep getting ahead of a brilliant story. To be fair to the author, numerous challenges plague self-publishing. The most recurrent being the astronomical costs of hiring competent proof-readers and copyeditors with a keen eye for detail. To a large extent, this is a structural problem that has been exacerbated by mainstream publishers who have been accused of taking an eternity to respond to authors, or even acknowledge receipt of manuscripts.

In such frustrating circumstances, some writers have chosen the path of embracing foreign publishing firms, most of whom, as testified by successful African authors across the continent and abroad, are quick to respond and offer relevant editorial advice. Others, like Nyachwani, have founded their small publishing houses — Gram Books (the publisher of “Sexorcised), which according to him, is one of the effective strategies of counteracting the domination of traditional publishers, a majority of whom have remained stubbornly conservative much to their detriment. This does not mean self-publishing is a licence to get away with murder, which in this regard, still involves taking due diligence in cleaning copy before it gets to readers. Also, while the narrative reads very fast, which is a stylistic strength, it is also a weakness in the sense that the writing, can at times, become too simplistic and shallow.

These weaknesses are bearable distractions. They do not in any way deny “Sexorcised” its cultural merit which is a profound meditation on the institution of modern marriage and the challenges that come with it in the 21st century. The stylistic range of the author also matches the central message, and thus, it should be read not just by ordinary Kenyans, but also by policymakers in various cultural and social institutions. Such a noble step might enable us as a nation — I want to speculate — reimagine the socio-cultural consciousness of our society that is trapped between the tensions of modernity and African traditions.

The book retails at Kshs 1000 and is available at Nuria Bookstore and Book Lounge. Or call: